Women in the 1990s with false-positive results after mammography screening had a 67% greater subsequent absolute breast cancer rate compared with women who had negative test results. However, with the advent of newer screening technologies in the first part of the next decade, the cancer rate was not statistically significantly different between the 2 groups, indicating that more of the positive results were "true positives," and that false-positive results were reduced. The findings are reported in the April issue of the Journal of the National Cancer Institute.

In a news release accompanying the publication, the journal highlighted the increased cancer risk after a false-negative mammography result in the earlier period, but failed to note the good news that newer technology has apparently overcome the earlier deficiencies in screening, which resulted in more false-positive results and may have led to more invasive testing and greater patient anxiety. Lead author My von Euler-Chelpin, PhD, associate professor in the Department of Public Health at the University of Copenhagen in Copenhagen, Denmark, and colleagues used data from between 1991 and 2005 from a long-standing, local population-based screening mammography program.

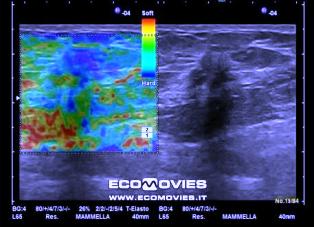

They determined the subsequent risk for breast cancer (including ductal carcinoma in situ) in women with false-positive tests. A false-positive test was essentially an abnormality detected by mammography, but not confirmed by subsequent testing. The analysis included 58,003 women (631,039 person-years at risk) aged 50 to 69 years. All underwent screen-film mammography, with independent assessment by 2 radiologists. Suspicious findings were followed-up using a triple test consisting of clinical examination, mammography, and needle biopsy. After 1991, mammography was supplemented with ultrasound of lesions, and ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration or histologic biopsy was used in all assessments. High-frequency ultrasound was used from 2001 onward, and stereotactic biopsy was introduced in 2002 for suspicious findings that could not be found by ultrasound. If breast cancer was ruled out, women were referred back to routine mammographic screening. Findings of breast cancer led to referral for treatment. In the event of a lack of consensus, surgical biopsy was recommended. Women with a diagnosis of breast cancer before the start of the study were excluded.

Screenings were conducted every 2 years, and women with a false-positive finding in a previous round were excluded from analysis in subsequent rounds. With a mean follow-up time of 10.9 years, and adjusting the results for age, the absolute cancer rate for women with negative tests was 339/100,000 person-years at risk. Women with false-positive results had an absolute rate of 583/100,000 person-years at risk, giving an adjusted relative risk (RR) of breast cancer for women with false-positives of 1.67 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.45 - 1.88). These results were consistent for women with false-positive results aged 50 to 59 years (RR, 1.65; 95% CI, 1.40 - 1.95) and those aged 60 to 69 years (RR, 1.69; 95% CI, 1.42 - 2.01) when compared with women with negative results in their age categories. In the 2 years after a false-positive result, there was no statistically significant difference in breast cancer between the 2 groups, leading the authors to suggest that the 67% higher risk among women who had had false-positive findings was not the result of interval cancers. However, the RR was significantly increased at 2 to 4 years after a false-positive finding (P < .001), but not at 4 to 6 years (P = .11). At 6 or more years after a false-positive test, the RR estimates varied from 1.58 to 2.30, which were statistically significant. Newer Technologies Associated With Fewer False-Positives The introductions of high-frequency ultrasound in 2001, stereotactic biopsy in 2002, and bidirectional mammography as standard procedure in 2004 were associated with a better detection rate for breast cancer and a lower rate of false-positives. To assess the cancer rates before and after these technologies came into use, investigators compared women screened between January 1, 1994, and December 31, 1998, and followed-up until December 31, 2000, with women screened between January 1, 2001, and December 31, 2005, and followed-up through December 31, 2007. Women in the first period with a false-positive test had a higher age-adjusted relative risk for breast cancer vs women with a negative test (RR, 1.65, 95% CI, 1.22 - 2.24; P = .001). However, for the later period, there was no statistically significant difference between the women with false-positive vs negative findings in their subsequent breast cancer risks (RR, 1.31; 95% CI, 0.87 - 2.00). The authors write that their findings indicate "it may be beneficial to actively encourage women with false-positive tests to continue to attend regular screening." Dr. Hudis responded by asking rhetorically whether that meant that other women should not be encouraged to do the same, and noted that "this is all kind of not getting to anything with pragmatic importance."